Неохо́тная Энаричка

Notes on books I'm reading, podcasts I'm following, music production, digital art, food, and more.

Inclusionary Zoning in Pittsburgh, Housing Policy, and You: a new blog post series

Part One

Happy New Year! My first blog post in a while. There's a housing advocacy group called Pro-Housing Pittsburgh that I've been involved in on and off for the past year; I've given testimonials at city council meetings and written comments and feedback on municipal government projects. Work has drained tons of energy from me so I haven't been as involved as I'd like to be, but one of my 2025 goals is to be more active at PHP. Housing policy is an issue I'm pretty passionate about, and it's where I feel like I can make the biggest difference in improving people's lives in cities (along with public transit and bike infrastructure). Housing policy is also heavily controlled by municipal politics and pretty insulated from federal politics, which is a big perk IMO.

(By the way, we meet monthly on Thursday evenings - the January meeting is tomorrow at 6:30 at the JCC in Squirrel Hill. Come join us!)

This is a study that some group members did on the effects on housing prices of (mostly) unsubsidized inclusionary zoning in Lawrenceville vs. neighborhoods without IZ - basically, government mandates to developers that X% of units must be rent-controlled, with no subsidies offered by the city to cover any of the difference between the market rate and the rent-controlled rate. The full study is available here.

In this Part One, I analyze and review the info reported in the paper, providing an initial draft summary and interpretation.

With that preamble out of the way, let’s dive in.

As mentioned in the abstract, Pittsburgh implemented IZ in Lawrenceville in 2019, Polish Hill/Bloomfield in 2021, and Oakland in 2022, requiring 10% of units in projects 20 units or more to be rented or sold as “Affordable Housing.” What’s their definition of AH? Per Deb Gross’s legislation:

- Rent capped at 30% of monthly income for households under 50% of Area Median Income (AMI) – households over this limit are ineligible for AH.

- Households whose income grows past this limit can stay until it hits 80% AMI, when they must leave.

- Mortgage capped at 28% of monthly income for households under 80% AMI (assuming 5% down on a 30 year)

Seems nice doesn’t it? Who doesn’t love making shelter cheaper for struggling households? Well...we’ll come back to this.

I mentioned that IZ was mostly unsubsidized in Pittsburgh. The city did offer a tax break they called LERTA (Local Economic Revitalization Tax Abatement). Developers bound by IZ could write off up to $250K of development outlays, although developers voluntarily providing AH in non-IZ neighborhoods could claim LERTA too. What was the effect of this? The study doesn't seem to directly address this - I would've liked to see an analysis of how much of the gap between market-rate and AH rate was covered by LERTA on average.

Deb Gross claimed that IZ led to a higher per-capital rate of development vs. non-IZ. Ed Gainey wants to expand it citywide. And that claim is what this study sought to investigate. Now that we’ve set the stage, let’s go to the study authors’ case for building more market-rate housing. Here’s a quote from the paper that summarizes their hypothesis.

For every 100 new market rate units that get built, 17 to 40 bottom-quintile income units become available within 3 years (Mast, 2023). As people move into new market rate units, they leave their former units vacant, allowing other people to move into their now vacant units, leaving still their own units vacant in turn, and so forth. We can think of these as “moving chains”, with each step in the chain a household moving from one unit to the next. These chains move rapidly - six steps in six months to four years. This effect is known as “filtering”, which describes the chains of moves that result from higher-rent units being built while creating vacancies for lower-rent units.

And what about the units vacated by poor folks? With no one “below” them to occupy those units, you suddenly have a bunch of vacancies...and those vacancies drive market rates downward.

“Research has shown that every new large building decreases nearby rents by 6%, relative to that building not being built (Asquith et al., 2023). This is the result of the “filtering” described above.”

Sounds great! But how does IZ affect this? Since offering rent-controlled units decreases the building’s revenue for a developer, this makes the project less viable. Housing developments that are just barely viable with entirely market-rate housing don’t get built at all. And so the filtering process above doesn’t happen. The net result is that, while the poor folks who manage to snag a prized AH unit get housed...the market rate does not change at all, meaning that anyone who can’t afford a market rate unit and can’t get into an AH unit doesn’t benefit.

The supply contraction caused by IZ is pretty rough. The authors quote a study that states “a 5%-7% decrease in revenue means a 8.75% to 16.75% reduction in new housing supply among buildings of 20 units or more.” Meaning that the market rate can actually go up in IZ areas, canceling out the improvement in housing for AH-protected people, and making the filtering chain described above work backwards.

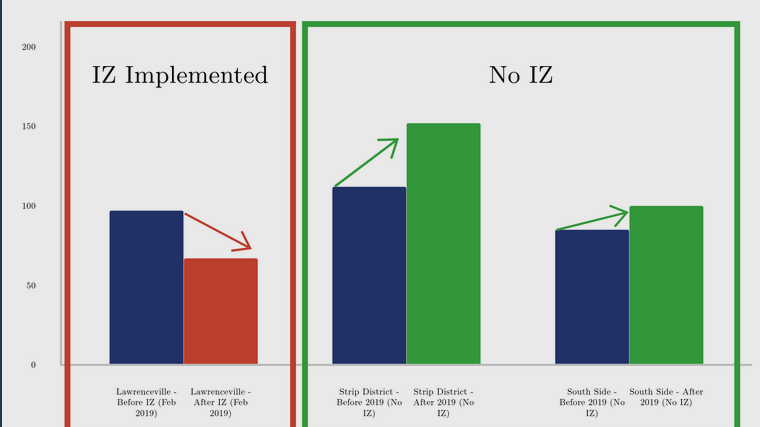

Next up, we dig into the data gathered by the authors. Here’s the summary plot they provide.

That doesn’t look good.

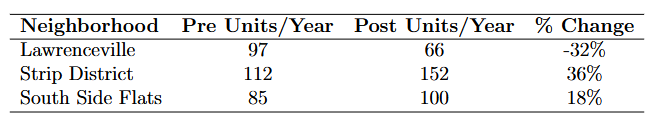

The authors used two control neighborhoods without IZ (South Flats and the Strip District) and examined completed units before/after Lawrenceville’s IZ implementation. How does this look on a per year basis?

A steep drop for Lawrenceville, and an increase for the controls. Are these reasonable control neighborhoods? The authors justify it through several points, including riverfront location, similar flat topography, the presence of an anchoring mixed-use main street, a similar mix of residential/commercial/industrial land uses, and broad economic revitalization in all three neighborhoods during the 21st century.

Interestingly, they don’t analyze changes in rent/sale prices in these neighborhoods during this time period. Perhaps an opportunity for future work?

The authors recommend repealing IZ altogether, but offer four adjustments as a compromise to IZ supporters if repealing it is not feasible.

- Make IZ voluntary (self-explanatory)

- Pair IZ with large-scale upzoning (increasing height limits, reducing setbacks, eliminating parking minimums, etc.) Zoning reform deserves its own blog post which I’d love to tackle in the future!

- Subsidize IZ to help developers cover some or all of the difference between the market rate and the AH rate

- Offer expedited and simplified project review and approval for developments complying with IZ.

In my next post (Part Two), I’ll try to critique some of the assumptions made by the authors, address confounding factors they may have missed, and propose future directions for study. In Part Three, I’ll try to anticipate and engage with leftist critiques of market-oriented mechanisms for increasing housing supply and lowering rents (I suspect that the “filtering” mechanism will draw some criticism), and then try to offer a “synthesis” in which liberal and leftist approaches to the housing crisis can function together and even reinforce each others’ effectiveness. If I have the time/energy for it, I may do a Part Four that critically examines the papers cited in the IZ study.

I hope you enjoyed this discussion. If anyone has comments to offer, I'm always glad to talk housing (and public transit, and bike lanes!) with interested folks. It's fun to get into the weeds of policy, and hopefully I've been able to share some of my passion for making housing more affordable here in Pittsburgh, even if we might not see eye to eye on the exact solution.

What's next?

Meta

I haven't had much motivation to post here as of late. The election is only a small part of it - just had too much going on in life, and have been losing interest in keeping up with this blog as a writing exercise. I'm still reading (1491 and other books), making music, and being social, but seasonal depression has been creeping in and between 40 hours of work and the rest of life, writing is taking a back seat as a hobby for now. But for the few people who read this blog, I thought I may as well offer a road map of future posts. Not all of these will be written and posted, and there's no particular order or target date; it'll happen when it happens. But here are some ideas I've been thinking about...

Posts that may or may not happen at some indeterminate point in time:

- The first 1491 entry. I'm still reading it! I have thoughts and notes. I'll start posting them eventually...

- Mom's borscht and frikadelki recipes.

- The Housing Theory of Everything - a long post series that will explain why housing is a critical issue with massive downstream impacts, and how to fix it with a blend of market-oriented and public policies.

- A post on how to make the US electoral system suck less (and why many people's perceptions of electoralism are colored by the uniquely awful American system)

- A post on the sewer socialists of Milwaukee, and why their public works-focused, reformist approach is more powerful than one might expect (with other examples of municipal socialism in practice)

- Vivi's favorite baking recipes, and a primer on cooking with exotic Theobroma species (there's more to this genus than just the cacao we know and love!)

- A quick primer on FL Studio and how you too can dive into the fun and exciting world of electronic music production.

- And other ideas TBD.

Stay tuned. Love y'all.

Buckwheat Блины (Blini)

Recipe

As part of an intermission between my last book and 1491, Vivi will be sharing some tasty family recipes. This one is for buckwheat blini, a classic Eastern European pancake similar to crepes in thickness and texture. Blini are widely enjoyed throughout Ukraine, Russia, and elsewhere in the Slavic world. Blini are commonly served with toppings both savory (smetana, cheese, cold cuts, butter, vegetable spreads, ground meats, salmon, even caviar) and sweet (varenye and similar jams/jellies, tvorog, fresh or cooked fruit, syrup, and more) Buckwheat is not the only flour used for blini (wheat and rye are common as well), but it's a popular one, and lends a delightfully rich, toasty, and nutty flavor to the blini. Here, I present to you my family's blini recipe.

What you need:

- 100g flour (I like to use 50/50 wheat/buckwheat)

- 25g flaxmeal

- 15g brown sugar (I've used maple sugar or syrup too - even honey can work)

- 5mL (1 tsp) vanilla extract

- 25g buttermilk powder

- 5g (1 tsp) salt

- 200mL warm milk. Use whole milk for richer, creamier blini, or skim/fat-free for a less decadent result. Feel free to substitute plant milks of any sort (I like oat)

- 2-3 large eggs. Vegan substitutes may work here but I've never tried them.

Optional extras:

- Various dessert spices (cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, cloves, etc.) to taste. I like a total spice load of about 1 tsp, but you can go as high as 3 tsp for intense flavor.

- 25g rolled oats. These can replace the flaxmeal, or supplement it for extra crunch.

- Buttermilk powder may be replaced with fresh buttermilk, plain greek yogurt (as with milk, customize the fat content to your liking), or smetana (available at European speciality grocers - you can ubstitute regular sour cream if you don't have one of these nearby)

- 5mL (1 tsp) vanilla

How to make blini:

- Combine the dry ingredients.

- Beat eggs, add milk, and then add mixture to dry ingredients. Batter should be fairly runny.

- Add butter or olive oil to a pan (or use spray can oil) and heat on low until a drop of water added to the pan sizzles. You can use any size pan you like based on how big you want each blin to be - I typically use 8 inches.

- Ladle a portion of batter into the pan, spreading it so that it just about covers it all.

- Watch the batter as it cooks; once it has just about set, then flip and cook until that side has just about set. Flip again to check the initial side, and then place on a plate.

- If the first few blini are misshapen, over/undercooked, or otherwise off, don't fret! There is a Russian saying that goes "Первый блин — всегда комом" (pervyj blin vsegda komum), literally "the first blin is always lumpy." Figuratively it means "everyone makes mistakes early on when trying something new." Keep at it, and you'll improve in no time!

Serve hot and fresh with toppings of your choice. 🇺🇦 💖

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, by David W. Anthony

Conclusion

David Anthony takes us through the endless Eurasian steppe on an archeological adventure to explain the origins of the Indo-European peoples who would come to settle and dominate a stretch of the Old World spanning from the Atlantic coast of Iberia, through Europe, into Anatolia and much of the Near East, and vast swaths of Asia up to the Urals and south into northern India.

He delves into remarkable detail on archeological findings (paired with linguistic reconstructions) of the Yamnaya horizon and its numerous daughter cultures, highlighting aspects of materials, burial practices, weaponry, jewelry, tools, and countless other artifacts, drawing fascinating conclusions about what these findings said about the cultures that lived there. It is this level of detail that makes his analyses so compelling - although the writing becomes dense at times, once Anthony has introduced the reader to one type of analysis, it gets easier to follow as he generalizes it to multiple cultures later in the book (for instance, his analysis of kurgan burial styles).

Anthony also does a good job illustrating cause-and-effect relationships and how they manifest in the archeological record (for instance, evidence of the transformative effects of wagon building, horse domestication, bronze smelting, etc. on societies, and how societies that adopted these innovations pressured and changed their neighbors in turn). References to Holocene climate changes as a driver of societal change/migrations were also appreciated. I especially appreciated his discussion of social and ritual practices, which helped bring these cultures to life in a way that can feel more relatable vs. discussion purely of economic and industrial aspects

Lastly, I appreciate when Anthony includes qualifiers and caveats about what the evidence can't explain, or the limitations of what the record reveals. Highly specific and detailed claims come with highly specific scopes, and I appreciate that he doesn't fall into the pitfall of "grand history" explanations that try to offer One or Two Big Milestones That Changed Everything and Apply to All Cultures.

The only minor nitpicks I had were a few geographical oversights (we don't hear much about the Indo-Iranians who pushed further south into the Indian subcontinent, or about Europeans from the Westernmost parts of the continent, beyond the Corded-Ware culture in present-day Poland/East Germany). But considering the massive scope of the book, it's understandable that he couldn't touch on every single Indo-European daughter culture. I sometimes wish there were a bit more exploration of the languages potentially spoken by the daughter cultures, but by his own admission, Anthony is not a linguist and so he may have been treading carefully in a less familiar field. Finally, his prose is on the drier and denser side for a book aimed at (educated) lay audiences, but given the scale of the topic and the rigor with which he is treating it, it's not a major mark against him.

Overall, The Horse, the Wheel, and Language is an outstanding dive into Proto-Indo-European history, and I hope that I can find similar books on other early world cultures. ★★★★.5 (4.5).

I'd like to sincerely thank everyone who's been reading and following along with me. It's been a pleasure to share what I've learned with y'all and a wonderful chance to practice my note taking and summarization skills. My next read will be 1491:New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus followed by Land and Liberty: Henry George and the Crafting of Modern Liberalism, and I look forward to sharing my reading with yinz again real soon.

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, by David W. Anthony

Part Five

Next we move onto the Sintashta culture, a culture of the Southern Urals notable for deploying advanced bronze metallurgy on an unprecedented scale. Every house had ovens, forges, slag, and copper, along with some of the oldest chariot remnants known, whole horse sacrifices, and bronze weapons dating 2100-1800 BCE. Some of the graves are remarkably similar to rituals described in the Vedic Rig Veda—a tantalizing link between the Sintashta and the peoples who would become the earliest Vedic cultures of Northern India. Graves often contained wounded or dismembered men. Sintashta settlements were also heavily walled and fortified, which, together with the metallurgy and chariots, suggests a major expansion of warfare in this area.

Around the Aral Sea was another pair of cultures: the Kelteminar and Botai-Tersek. These were pastoral gatherers, who were sedentary, but did hunt bison, boards, and camels, fished, and gathered apricots and pomegranates. This group was displaced by Sintashta migrants, possibly due to climates becoming cooler and more arid, and concurrently we see these Aral cultures adopting many Sintashta traits (metallurgy, walled settlements, etc.). Finally, we see signs of greatly increased trade with the Near East and Mesopotamia—likely from these cultures seeking copper. The centralization and early statecraft seen with increasingly large, fortified, and specialized settlements may have been from a positive feedback loop due to increased warfare made possible by advancements in chariotmaking and metallurgy.

Finally, there is discussion of the Srubnaya culture, a southern neighbor of the Sintashta, who traded turquoise, tin, pottery, blades, mirrors, and beautiful silver and gold artifacts and figures all throughout the Near East, including contacts with Mesopotamian states like Akkadia and Elam. Srubnaya (and similar cultures collectively called “Bactria-Margiana Area Cultures”) artifacts have been found as far west as Syria, reflecting the rapid expansion of trade between the steppe and the Middle/Near East around 2100-1800 BCE. These artifacts were also found up north in the steppes, illustrating that the BMAC had become a valuable conduit for trade throughout Central Asia.

There is so much (much) more to discuss in Anthony's work; there is honestly enough material for another four blog posts of similar length and depth. However, in the interest of brevity and time, we will leave off here and proceed to our conclusion.

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, by David W. Anthony

Part Four

At last we pick up from the Yamnaya incursions into Tripolye territory mentioned in part three. Anthony offers one possible explanation for the outcome of these incursions—a lord and client/vassal relationship (from here referred to as the Usatovo culture), in which Yamnaya steppe cultures became chieftains/high status leaders whose burial practices were emulated by their subject peoples (perhaps to cement the social hierarchy that the Yamnaya culture had built), while Tripolye artisans continued to produce the materials and artifacts (wool clothing, cereal farming, glassworking, etc.) albeit with Yamnaya flourishes (best seen in pottery, which was a mix of Tripolye base designs with Yamnaya decoration).

There were even clay sculptures painted red, but with non-ochre (iron oxide) pigments, as hematite was not readily available around the lower Danube, another sign of cultural syncretism (ochre-painted items are a hallmark of Yamnaya culture; the newcomers sought to replicate these items with unfamiliar pigments). There were also cannabis seeds—again, not native to the area, but likely brought over by Yamnaya migrants.

In particular, Usatovo sites had three different sized kurgans. The largest housed only adult men with various ornate jewelry and pottery (perhaps a nobieman/patrician class, as the skeletons show no signs of battle injuries), the mid sized had metal weaponry (warriors and kin), and the smallest was not a kurgan at all, and housed men, women, and children alike, with few ornate artifacts. One last item of note. Graves were often marked with wagon wheels and wolf-themed jewelry, stelae, and belts—consistent with a reconstructed PIE myth in which new warriors were initiated by launching cattle raids into neighboring territory, dressed in wolf-themed attire, as if mimicking packs of wolves on the hunt.

My next book, and testing a polling feature

Introduction

I'm nearing the end of David Anthony's excellent work. I'm still putting together my future blog posts about it (probably two more plus maybe a concluding post), but in the meantime, I wanted to solicit recommendations for my next read. You can vote in the poll below.

Bernstein, Luxemburg, and Revisionism in pre-Revolutionary Russia

Introduction

I've been reading through Luxemburg's Organizational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy and Bernstein's Evolutionary Socialism to try to articulate some thoughts on how Revisionism may have played out in Russia during its revolutionary period, and whether it would've been successful at advancing socialism in Russia over the long-term. As I'm fairly new to exploring Marxist philosophy, please bear with me if I misinterpret or otherwise make any mistakes. These are early and loosely organized thoughts that will be part of a series in which I try to summarize and offer my take on the many different leftist factions and movements vying for power before, during, and after Russia's revolutions.

Bernstein, Luxemburg, and Revisionism in pre-Revolutionary Russia

Part One

My very tentative thoughts are that reformism and non-vanguard approaches would've probably enabled a more stable foundation for Russian leftism long-term, in the sense that:

- 1) A worker base that has experienced first-hand the benefits of incremental leftist policies would be primed to fight for more radical socialist movements. Basically, that smaller scale, pragmatic "sewer socialism" would energize grassroots support for revolution rather than pacifying it.

- 2) A decentralized movement composed of many local labor organizations and party cells is more flexible and adaptable, able to learn what policies and tactics work best in their area and among their populace; a central authority directed by a group of vanguards who try to channel instructions down through layers of hierarchy to these local organizations would be inflexible and unable to respond adequately to the needs of local movements. This would've been especially important in Russia given the sheer geographic size and population of the country.

- 3) A central authority is easily hijacked by charismatic, power-seeking people who know how to speak the "language" of a socialist movement, but who instead have the goal of enriching themselves and their clique. And a central authority rushing forward with the urgency of revolution would have less time to root out and safeguard itself against such opportunists. Lenin argues that opportunism arises from intellectuals taking advantage of disorganized and decentralized groups; Luxemburg argues the exact opposite in her work, and I'm inclined to believe her given the long-term outcome of the October Revolution.

- 4) I find Bernstein's critiques of Orthodox Marxism in Evolutionary Socialism were pretty insightful. He makes a few prescient points: a) small/medium scale businesses in some industries have unique advantages that outweigh benefits of economies of scale, b) scientific and technological advancement is continuously creating new markets and economic sectors where smaller capital owners spring up before larger owners take notice, and c) the power structures created by liberalism can readily be co-opted and leveraged for socialist goals in a way that feudal and autocratic power structures could not. Revolution was necessary and crucial for toppling tsarist autocracy, but the Russian Republic that rose in its place could be transformed into a socialist one without further revolution.

With further reading I'm also seeing that Luxemburg and Bernstein were at odds in many respects, with Luxemburg seeing Bernstein as excessively revisionist himself, but I'm still parsing their differences.

Bernstein, Luxemburg, and Revisionism in pre-Revolutionary Russia

Part Two

So why did the Bolsheviks specifically did so well given the apparent advantages of Revisionism? From my perspective, it is because tsarist autocracy kept a tight grip on Russia until the very last minute. The exceptionally reactionary, stubborn, and outright incompetent rule of Nicholas I and II (especially the latter's complete refusal to cede any power to the Duma) prevented any of the institutions of liberalism from taking root at all. By the time the tsar finally abdicated in the February Revolution, the Russian State had already effectively collapsed under the strain of war. The Provisional Government inherited a smoldering ruin of a country, with a populace facing profound starvation, sickness, and general human suffering; Kerensky made it even worse by launching a disaster of an offensive when his first priority should've been to make peace as soon as possible and to deliver emergency aid to the populace by any means necessary. Under such dire conditions, a fast, radical, centralized, charismatic, and decisive vanguard will thrive. Hence, Bolshevik victory and control of Russian leftism post 1917.

In a scenario where things go even slightly better for Russia (Alexander II isn't assassinated and his successors allow liberal reforms, Nicholas II actually cedes significant power to the Duma and 1905 Constitution, Kerensky pulls the Russian Republic out of the war early and treats the suffering of his people with the urgency it deserved, etc.)... I think that's where the revisionists would have the most success.

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, by David W. Anthony

Introduction

In this book, anthropologist David W. Anthony discusses the origin of Indo-European peoples from the Pontic-Caspian steppe and their language and culture. He describes how they migrated into Europe and interacted with the prior population there and explains the archeological and linguistic evidence that grants us valuable insight into how these ancient peoples lived, as well as the limitations of our knowledge and any unanswered questions. In particular, Anthony focuses on how Indo-Europeans domesticated the horse, invented the wheel, and developed advanced bronze metallurgy, and how these technologies enabled sweeping social and political changes in IE society.

I'll be writing a series of posts that summarizes what I've read as I progress through the book, offering notes and commentary.

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, by David W. Anthony

Part One

I'm about a quarter of the way through and still taking in/processing the information covered in the book, but so far I've really enjoyed the use of comparative linguistics to a) narrow down the "original homeland" of Proto-Indo-European speakers based on reconstructed environmental words, and b) make predictions about their culture based on vocabulary and comparing it to archaeological evidence.

There is also some interesting discussion on the nature of cultural, ecological, and linguistic divides and how they don't always correlate (several peoples can share cultural traits but have very different languages, while the reverse - divergent ancient cultures sharing a language - is much rarer). Interestingly, the most conclusive information about ancient peoples' cultures and languages often comes from ecological borders - in areas of transition between different biomes, peoples on either side of the boundary will develop especially strong differences between each other, and this manifests in markedly different artifacts (pottery, house styles, etc.) right on either side of the border.

I'm currently reading through a chapter that describes how early Anatolian farmers migrating to Greece/the Balkans and up into the Pontic steppe interacted with existing forager peoples and how this contact manifests in local archaeology.

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, by David W. Anthony

Part Two

About 1/3rd done, and I'm currently reading about horse domestication. There are several clues archeologists have used (such as gender/age/size distribution of slaughtered horses, used to distinguish wild herd hunting from pasture-raised horses), but the keystone has been bit wear on horse teeth.

Bitting leaves beveled wear on specific teeth from the horse chewing on the bit - metal bits wear more, but even older bits made with softer material will erode enamel. Researchers compared horse teeth from different dig sites to modern horses that had been bitted for varying amounts of time, and, were able to pinpoint where and when different steppe societies domesticated horses based on the observed enamel erosion + carbon dating of the samples.

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, by David W. Anthony

Part Three

Halfway through the book! It's a meaty read at 568 pages, but getting through it. I'll probably pick something lighter for my next read.

We're now discussing how "Old Europe" (the pre Indo-European cultures present before ~3400 BCE) gave way to Indo-Europeans. The author talks about how the combo of horse domestication and the invention (or possibly import from Mesopotamia via the Caucasus) of wagons around 3400 BCE enabled pastoral people of the Yamnaya Horizon to grow the number and territory of their herds.

This territorial expansion led to greater conflicts between neighbors about grazing land and greater stratification of wealth as some people accumulated much larger animal/land amounts. We see this change reflected in a greater disparity of wealth buried with people in cemeteries - a reliable hallmark of status was metal tools, jewelry, and artifacts (bronze, gold, silver, etc.) in graves. The author also hypothesizes that these new territorial conflicts spurred development of the Proto-Indo-European language, as a sort of common "trade/negotiation" language among Yamnaya peoples.

Movement of Yamnaya peoples from the Pontic Steppe westward into Europe may have been spurred in part by climactic cooling and drying, leading pastoralists to seek warmer and wetter territories in the west, and so we see Yamnaya-type sites mixing in and eventually replacing Tripolye sites (a classic Old Europe culture centered around the Danube) after 3000 BCE.

Even within the Yamnaya we see differences West to East. Western Yamnaya near the Dnieper River were more agrarian and sedentary, cultivating small cereal crop plots around relatively large settlements along with the usual cattle ranching. Lots of cattle - this is about the time when lactase persistence evolved in Scandinavia and rapidly spread south, enabling many more people to consume dairy regularly. Eastern Yamnaya in the Don-Volga Basin had more horses and sheep, and seemed to do more fishing and hunting.

Western Yamnaya also appeared to be more matriarchal than Easterners based on archeological findings. Evidently, the more patriarchal Eastern Yamnaya won out in linguistic influence, as PIE has lots of specific words for patrilineal relationships, but not as many for matrilineal ones.

There's also a brief digression about the Afanasievo culture - a group of Yamnaya migrants who journeyed all the way east across the Kazakh steppe to end up near the Altai Mountains. This is the opposite of pretty much all other Indo-Europeans, and no one really knows why they traveled that way. This group was the ancestors of the Tocharians, an Indo-European culture that lived in the Tarim Basin around 400-1200 CE, a Western outlier in a region otherwise dominated by Turkic, Mongolic, and Sinitic peoples.

Fun fact: many Chinese languages may have borrowed their word for "honey" from a Tocharian language (Tocharian B's mit, which came from PIE médʰu) . Mandarin mi is likely cognate with English mead, French miel, and Russian мёд (mjod).

Introduction

In which Vivi explains the purpose of this blog.

I read a lot. I am not particularly good at retaining what I read. This blog is a way for me take notes on my readings, share them with the world, and make recommendations for neat books that I think other folks might enjoy.

Posts I make

What will I post about? Read on below.

Book notes

As mentioned above, I want to share what I read with other people.

I tend to read a lot of non-fiction. Most of it concerns history, but I'll dip into other topics as well.

Music production

I make electronic music. Mainly atmospheric D&B, jungle, and other breakbeat music. I'll post about what I'm making, share production tips and tutorials, and snippets of work in progress.

Blender art

I also make digital art in Blender. Usually for music cover art.